Online exhibition «Jewish wife and her role in family»

Author: Natalia Prokopieva; Vice-Director, Main Keeper

As in any traditional society, the married state was perceived as the most ethical and natural in the Jewish community. Young people were to find themselves a match and get married for the “true value in life, for the Torah, for protection and peace.” Persons above the age of consent but still unmarried were treated without respect and suspected of being sinful. The primary predestination of man and woman was procreation, which was only believed to be possible in wedlock, as well as the fulfillment of many rites and ceremonies prescribed by Judaism in the household and in the family circle.

The woman’s role in parenting and in ritual practice was great, and her status in Jewish society was high. The humorous expression “Yiddishe momme” implying her care, her control over all family processes sometimes running to extremes, appeared for a reason. However, mother’s “suppressing” love and care was greatly caused by her continuous concern about her issue, and its beginnings are in turn in keeping centuries-old memory of “life in exile” and desire to preserve her people.

The woman’s role in parenting and in ritual practice was great, and her status in Jewish society was high. The humorous expression “Yiddishe momme” implying her care, her control over all family processes sometimes running to extremes, appeared for a reason. However, mother’s “suppressing” love and care was greatly caused by her continuous concern about her issue, and its beginnings are in turn in keeping centuries-old memory of “life in exile” and desire to preserve her people.

According to various sources, the age of consent was from 13 to 18; it was desirable for young people to get married just in this period. Folklore echoed the people’s ironical attitude, especially to girls failing to get married in due season, for instance, “an overripe maiden is like a last year’s calendar;” it was also believed that an unmarried girl of over twenty tempts men to sin.”

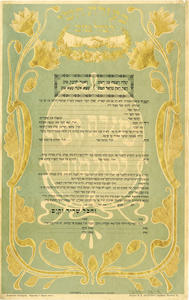

As soon as their children reached the age of consent parents started to look for a match, and when an agreeable partner was found, they made arrangements and sent a professional matchmaker to the bride. The groom and the bride could be acquainted, or saw each other for the first time during the betrothal. Families tried to choose a match from those equal to them in status; for the successful completion of a marriage transaction, the families’ lineage and wealth had no small share, since it was assumed that the parents of the bride or groom would have to support the young family for a few years. Along with the bride’s dowry size, it was set down in a written engagement agreement, which was called “tnoim.” It contained the terms and date of the wedding, it was a premarital record of the family’s pecuniary basis. By the late 19th and early 20th century, a ready-made form of such an agreement appeared, printed in a print shop, to be filled in and signed. On the top of the tnoim form, under the caption “With God’s help. Good luck,” an image of a handshake was placed, as a symbol of reached agreement.

The next document securing the marriage was “Ktubba,” a marriage contract, which the groom handed to the bride under the chupa; the wife kept and safeguarded it. It was a very important document listing the husband’s duties to his wife; for example, if it was lost, the spouses could not live together until a new one was written. According to the marriage contract, the husband undertook to maintain his wife as “worthy Jewish husbands” should. The Ktubba guaranteed the wife a certain amount of money in case of divorce, and other terms were also stipulated. The Ktubba’s text, although money-focused, was stated in a poetical language and adorned with quotes from the Holy Writ, illustrations to it, and zodiacal signs, which often turned the contract into a work of art.

Under the chupa, at the culmination of the wedding rite, the groom put the ring on the bride’s finger. At the end of the ceremony, it was common to break a wineglass in memory of the destroyed Temple in Jerusalem. For the ceremony, the bride’s mother baked a special wedding pie and gave it to the son-in-law; the pie was jokingly called “my Mommy’s sore spot.”

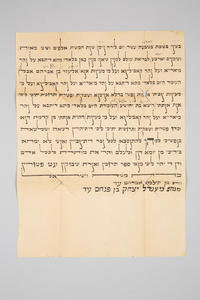

In Jewish society, in case of a husband’s death, levirate marriage was permitted to retain his kindred’s property: a childless widow could marry his brother. In this case, the woman’s consent was not required; only the brother-in-law’s willingness or unwillingness mattered. If the brother refused to marry, he had to perform the rite of “halitza,” literally “untying.” The ceremony was held in the synagogue, in the presence of a rabbinical court of law. The main part of the halitza rite was undoing by the widow the shoes of the brother-in-law refusing to marry her. Leaning his back on the wall, the brother-in-law puts forward his right foot in a purpose-made odd laced sandal; the widow, and then the brother-in-law pronounce the prescribed formulas in Hebrew, after which the widow bends down, unties his sandal string with her right hand, takes it off and throws it back over her shoulder, spits on the floor in front of him, and says in Hebrew, “Thus shall be done to the man who will not build up his brother’s house, and his name shall be called in Israel, ‘the house of him that hath his shoe loosed.’” Upon completion of the halitzah rite, the widow receives the so-called “get halitzah”, a document authorizing her “to marry whoever she desires.” The sandal was kept in the synagogue, and was let on hire.

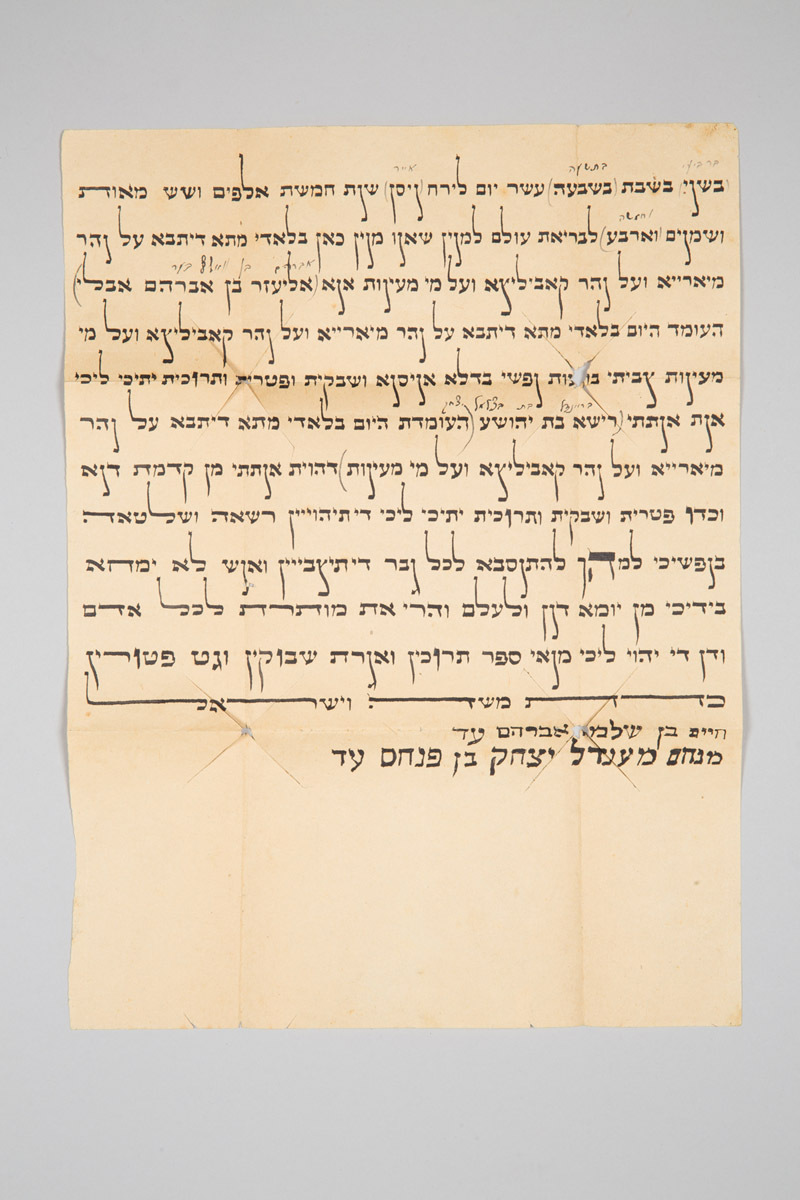

"Get” a letter of divorce

Dubrovna District, Vitebsl Province, 1924.

“Done in the shtetl of Lyady on the Mereya River, on Monday, 17 Nisan 5684.” (1924)

Husband Eliezer son of Avraham Aveli (?) divorces his wife Reishe (?) daughter of Yehoshua.

Witnesses:

Chayim ben Hirschel (?) ben Avraham

Menachem Mendl Yitshak ben Pinchas.”

A divorce could only be initiated by the husband in case of the wife’s childlessness or infidelity. The Torah’s words “…he shall write a letter of divorce to her” in Jewish law were interpreted literally: a get, a document relieving the woman of her marital duties, was drafted. A letter of divorce, like other documents in Judaism, had an established form in Hebrew, and contained the following information: the name of the town and river, the divorcees’ names, and names of attending witnesses. The letter of divorce was cut at four corners and kept in the synagogue archive.

Jewish costume of the Pale of Settlement was formed after the pattern of Polish urban costume in the 17th-18th centuries, and was also influenced by local East Slavic population, but visually differed from the Christian neighbors’ garments. As late as in 1841 the Russian government enacted that “… the Jews shall not differ from the others” in their clothing (as being Polish and not related to the Jewish religiosity). This edict was happily received by young Jews, who began to enjoy dressing smart and in an urban manner, since the Jews generally settled in towns and shtetls rather than in countryside. Married women replaced their heavy shawls with cotton headscarves on weekdays and with caps and bonnets on holidays, but still covering the front part of their head with hair and silk wigs, since married Jewish women had to shave their heads so that “the hair does not tempt any of the outsiders.” The essential women’s clothing was silk or cotton skirts and a blouse with a sleeveless vest – and with a brustichl, a breast decoration, on holidays. Three clothing components, brustichl, headgear, and apron were essential in the Jewesses’ costume; they were modified and modernized, but never disappeared from the costume. The brustichl, the most remarkable part of the costume in its festival version, had a cardboard base trimmed with silk, velvet, and brocade, and decorated with spangles, gold embroidery, tinsel yarn, insets of tinted glass and simulated pearls, and metalized lace or “shpanie” (Spanish).

The women’s headgear, i.e. caps, shawls, and headscarves, varied depending on fashion trends, but married women in shtetls continued to wear them with wigs following the religious tradition. The holiday costume was supplemented with neck and head decorations of mother-of-pearl, and natural or artificial pearls. They were preferred by married ladies, while unmarried ones preferred corals.

The function of women’s apron, as well as the gartel braided belt in men’s costume, was not so much pragmatic as symbolic, serving to protect her body “beneath.” When aprons were canceled from the town costume everywhere, orthodox Jewesses continued to wear the apron concealed under other clothes.

In general, the clothing of shtetl women was somewhat obsolete compared to town wear (with regard to demands of modesty) in the fit, materials, decoration and use of archaic shapes and articles of clothing.

The role of the Jewish woman in the family’s spiritual life was no less important than the man’s role. Her main duties in the home were the Commandments, the main of which were separating the challah (a piece of dough prior to bread baking), observing the “kashruth” (code of requirements for food and for cooking techniques), keeping the family life clean, and lighting candles.

Important rules of behavior at the table were stated in the Talmudic tractate “Derech Eretz” (“the way of the land.”) Its canons emphasize the importance of keeping to harmony in family life and attentive attitude toward wife, children, and relatives. The rules of derech eretz indicate that a man shall be polite, careful in words and demands, and avoid any obscene talk; he should eat less than his means permit, and dress decently. Derech eretz also requires observing the common decencies in table manners, receiving guests etc. There are multiple stringent prohibitions related to food. The main and only criterion of its suitability is not hygiene reasons but its compliance with the Torah canons.

To cook food, the Jews used kitchenware bought at fairs, that is, made by peasants and craftsmen at the place of their living. In doing so, separation of vessels for meat food, milk food, and water was strictly observed; kitchenware for different foods was also kept on different shelves. Apart from the utilitarian and aesthetic, food also had other functions. For example, bits of bread left on the table were intended to mollify spirits. Food containing onion and garlic, with their pungent odor, was used as protective amulet, and for practical purposes during epidemics.

It was a woman’s privilege to light candles, blessing with candle flames the advent of the Shabbat or the beginning of another holiday, and to make a Saturday’s loaf, or challah. The lighting of candles officially marked the start of sacred time for the home; once the candles had been lit, special restrictions applied or it was time to observe the holiday. Also, separation of weekdays from a holiday, and vice versa, was signified by inhaling spice aromas from special “goddes” (besamim) boxes. Jewish law does not prescribe exactly what spices are to be used, as long as they have an aroma (such as cinnamon or cloves). Sniffing it, the whole family passed a rite of purification. Silver incense vessels were favorite articles of Jewish jewelers. They were made shaped as Gothic turrets with little pennants and chime-bells, flower buds, little fishes, and even, paying tribute to new era trends, little cars and railway engines in the early 20th century.

The Shabbat begins and ends with lighting a fire. The rite is mentioned in the Mishneh Torah, being one of the essential prescriptions to be performed by women; richly ornamented candelabra were used for it, which often were paired. The whole ceremony is called Havdalah (“Separation”) and means separation of the holiday from everyday routine. The number of candles to be lit is not specified exactly, but as tradition demands, at least two are lit, and sometimes to suit the number of residents in the household. On Friday night, a flame symbolizes joy and light of the beginning day, and on Saturday night it implies returning to the everyday world where work is permitted. As late as in the early 20th century, it was believed in some Jewish communities that candle flame drives away various demons, notably Lilith, Agrat bat Mahlat and other evil ones, which became especially dangerous on the eve and the close of the Shabbat. Kindling flames on Saturday night comes with other symbolic rites and a prayer.

Amulet (“kame’a”) against difficult childbirth

Shtetl of Beshenkovichi, Vitebsk Province. Late 19th – early 20th c. Paper, watercolor.

The text is repeated twice, in the left and right part of the amulet:

“Adam and Eve. To expel Lilith, Senoi, Sansenoi, Sammangelof.”

The image and text are reproduced after “Raziel,” a mystic 11th century book that served as a kind of instruction for making amulets.

Amulet (“kame’a”) to protect a woman in childbirth

Shtetl of Beshenkovichi, Vitebsk Province. Late 19th – early 20th c. Paper, watercolor.

Text: “In memory of Adam and Eve, let Lilith, Senoi, Sansenoi, and Sammangelof,

Shamriel and Hasriel be expelled”.

Thus, the family values in a Jewish family were determined by the woman, who was in fact responsible for all that happened in the home and family life: procreation and child protection, observing rules and prescriptions in her folks’ behavior, meals, and home rites.